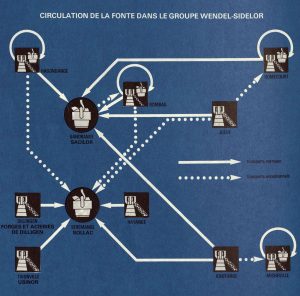

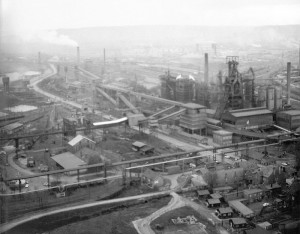

Der Osten Frankreichs war einmal das Land der Blasststahlwerke, nirgends auf der Welt arbeiteten so viele Konverter wie auf der roten Erde Lothringens. 1965 waren es noch 81, sechs mehr als in der BRD.

Im Oktober 2011 legte ArcelorMittal in Florange die beiden letzten still.

2018 wurde das (längst feststehende) endgültige Ende der Flüssigphase im Tal der Fensch verkündet. Das Stahlwerk wartet seit dem auf seinen Abriss.

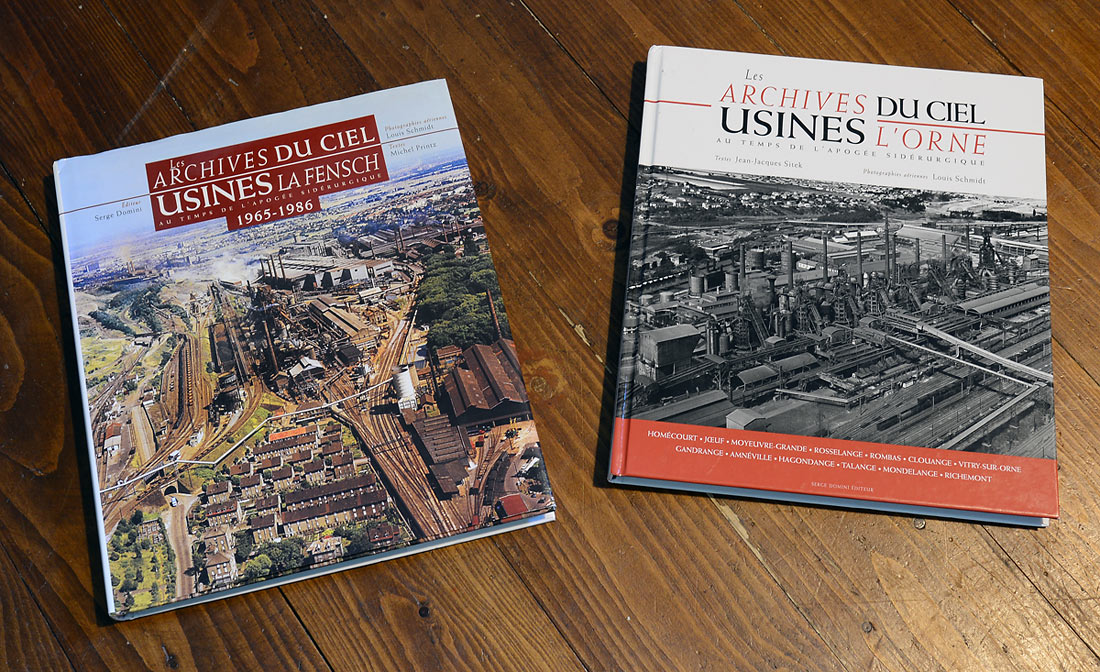

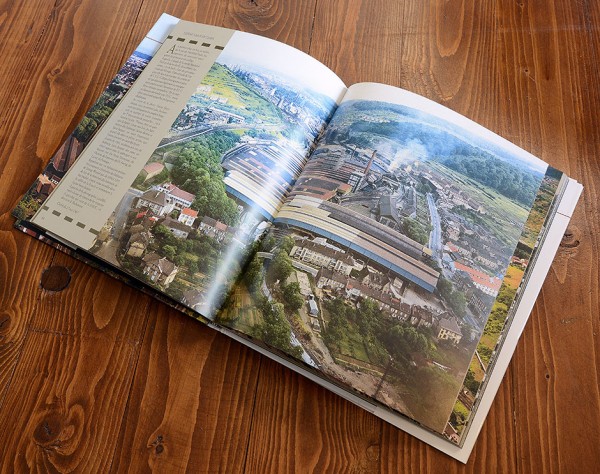

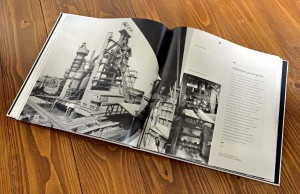

Der Komplex (inzwischen auch von der “Urbex”-Szene entdeckt) ist immer noch hochinteressant, birgt er doch Spuren von fünf verschiedenen Stahlwerken die die technische Entwicklung der Stahlerzeugung seit dem 2. Weltkrieg dokumentieren.

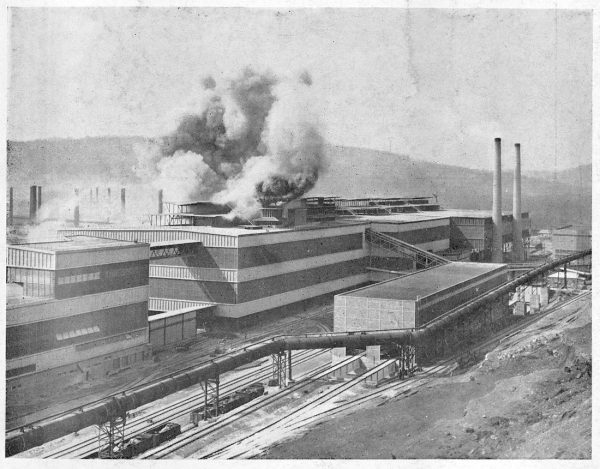

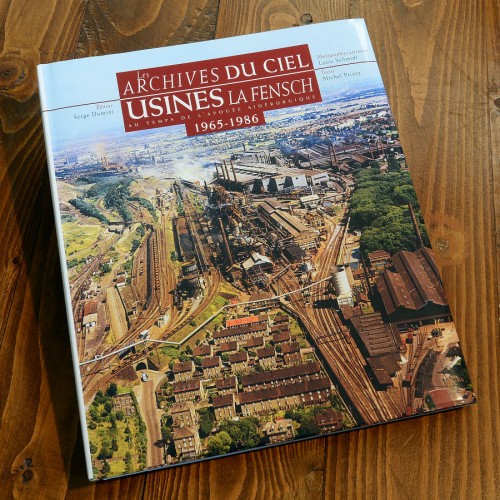

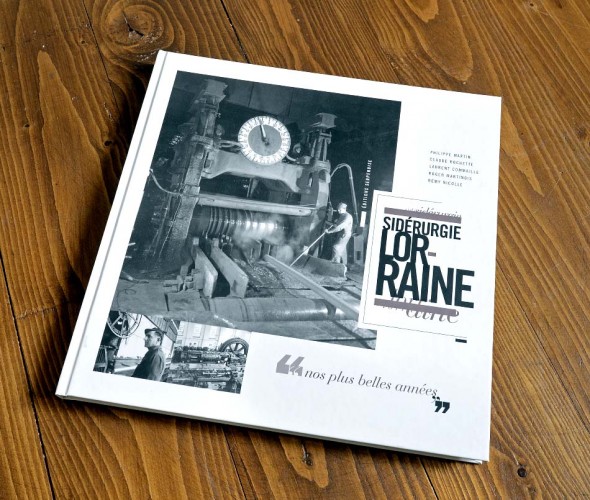

1948 war als Gemeinschaftsunternehmen verschiedener französischer Stahlhersteller die Société Lorraine de Laminage Continu (Sollac) gegründet worden. Ziel war es die immensen Investitionen für eine kontinuierliche Warmbreitbandstrasse nach amerikanischem Vorbild gemeinsam zu stemmen.

1954 ging das Walzwerk in Serémange im Fenschtal in Betrieb.

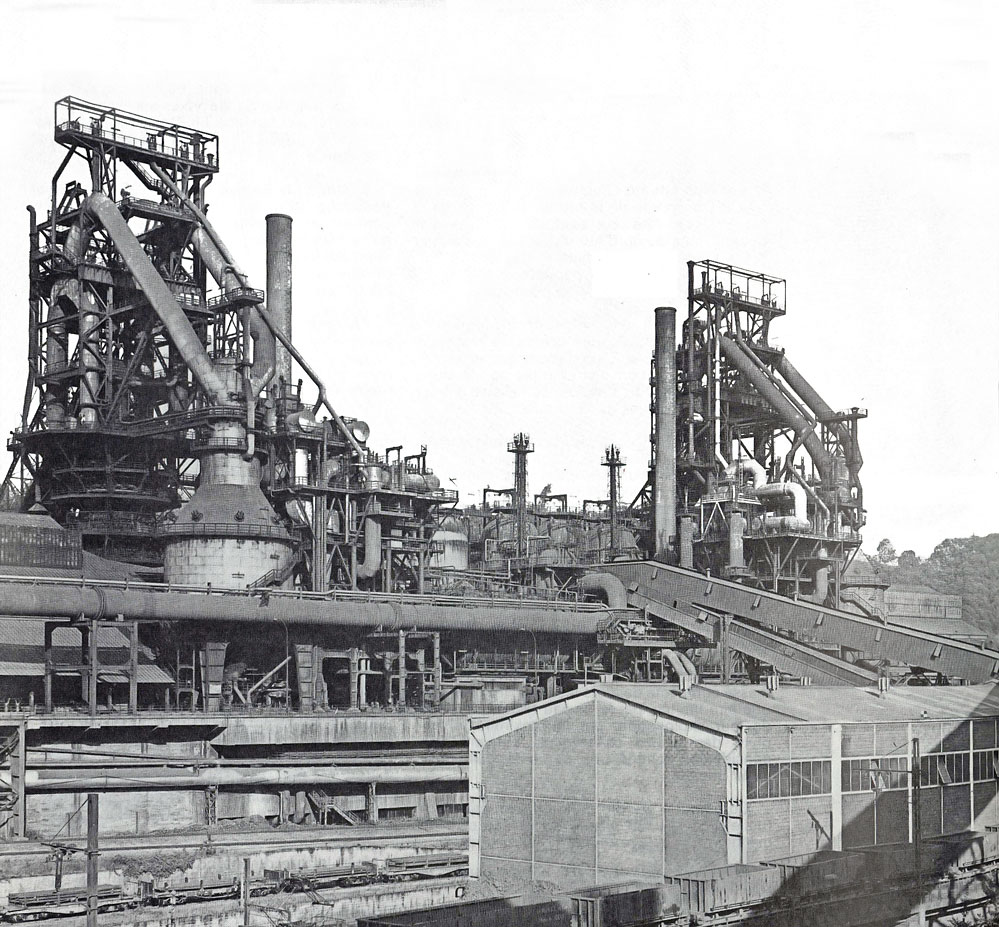

Um die neue Straße mit Vormaterial zu versorgen war geplant von der DEMAG, Duisburg im benachbarten Florange eines der größten Stahlwerke Europas bauen zu lassen.

Das kombinierte SM-Thomasstahlwerk sollte sechs Konverter und sechs Siemens-Martin-Öfen in Reihe umfassen. Gebaut wurden schließlich 4 Öfen und 4 Konverter in zwei Gruppen sowie drei Roheisenmischer. Das SM-Stahlwerk ging 1953 in Betrieb das Blasstahlwerk folgte zwei Jahre später.

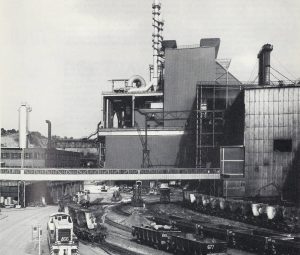

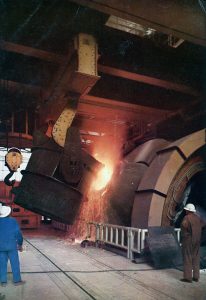

Da die Qualität des Thomasstahls für die Produktion von Feinblechen nur bedingt zu verwenden, der SM-Stahl verhältnismäßig teuer und das neue LD-Verfahren für die phosphorreichen lothringischen Erze ungeeignet war installierte Sollac anstatt eines fünften SM-Ofens ein Kaldostahlwerk.

Der dort um seine Längsachse rotierende 110 t Sauerstoffaufblaskonverter wurde 1960 wieder von der DEMAG geliefert.

Im Oktober 1973 baute man zu Erprobungszwecken den Thomas-Konverter 4 zu einem 65 t L.W.S.-Konverter um. Bei diesem in Frankreich entwickelten Verfahren (Loire-Wendel-Sprunk) wurden Sauerstoff und Kalk von unten durch die Schmelze geblasen, so ließen sich in ehem. Thomaskonvertern hochwertige Stähle auch aus der lothringischen Minette erzeugen. Nach einer erfolgreichen Testphase rüstete man dann Ende 1975 auch die übrigen Thomas-Konverter um.

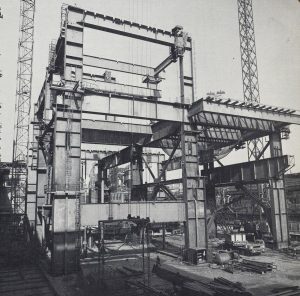

Ab 1976 begann dann die Planung eines zweiten L.W.S.-Stahlwerks mit 240 t Konvertern.

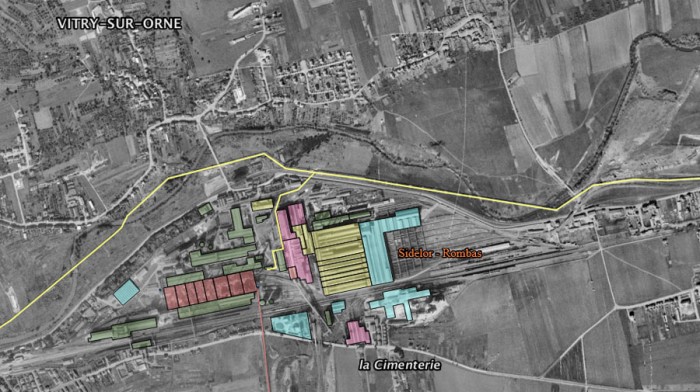

Dafür wurde noch im gleichen Jahr das alte SM-Stahlwerk stillgelegt und auf ein einem Teil seiner Fläche mit dem Bau der neuen Konverterhalle begonnen. Im Juli 1978 gingen die beiden L.W.S.-Konverter in Betrieb, ein zunächst geplanter dritter wurde nie gebaut.

Das kostenintensive Kaldostahlwerk legte die Sollac im Dezember 1978 still und auch das

L.W.S.-Stahlwerk 1 mit seinen vier 65 t Konvertern wurde im Sommer 1980 ein Opfer der Stahlkrise.

Von allen Stahlwerken und der Mischerhalle dürften heute noch Baulichkeiten erhalten sein, das L.W.S.-Stahlwerk 1 wurde etwa zur Hälfte (Konverter 3-4) abgerissen. Siehe Karte.